The story of Arkansas State's 1975 undefeated season

Rob Wiley sat down in his chair and placed his phone on the table in front of him. The phone shared the tabletop with a computer, a printer, and a handful of books. He opened his messages, hitting play on the audio file he had been sent. Boxes littered the floor of the cluttered, white-walled living room.

He had just recently moved into this new home in the suburbs of Houston, Texas, but he hoped the file would bring him back to Jonesboro, Arkansas.

Eight-and-a-half hours southwest of Jonesboro, Wiley listens to old tapes of Arkansas State football games. He’s not just listening for the action on the field. He is honed in on the broadcaster, critiquing him at every opportunity while taking notes in his head.

Trying too hard to sound like others. Develop your own persona.

When Wiley was young, he wanted to be the center fielder for the Los Angeles Dodgers. He quickly realized that baseball might not be his path, so he chose a new path to keep him in sports. He became the sports director at KARK-TV in Arkansas. Instead of covering the outfield grass at Dodger Stadium, he covered the gridiron at Arkansas State and other local schools. His work caught the attention of a certain Arkansas State board member: Mike Beebe.

Beebe, who would go on to become the governor of Arkansas, gave Wiley a call.

Beebe was interested in building a relationship between the school and Wiley’s news station. His initial pitch was to create a TV show. Wiley was willing to work with him, but wanted to become the play-by-play broadcaster for Arkansas State football. It had been a “lifetime ambition” for Wiley, and he was able to strike a deal in time for the 1975 football season.

Those old tapes he was listening to were his own. With the help of the son of one of the team’s former players, Wiley has been able to collect and review relics of the 1975 season. He knew his broadcasting was not perfect, but the team he covered certainly was.

“It just so happened that the first season I did play-by-play, they had this great undefeated football team,” Wiley said.

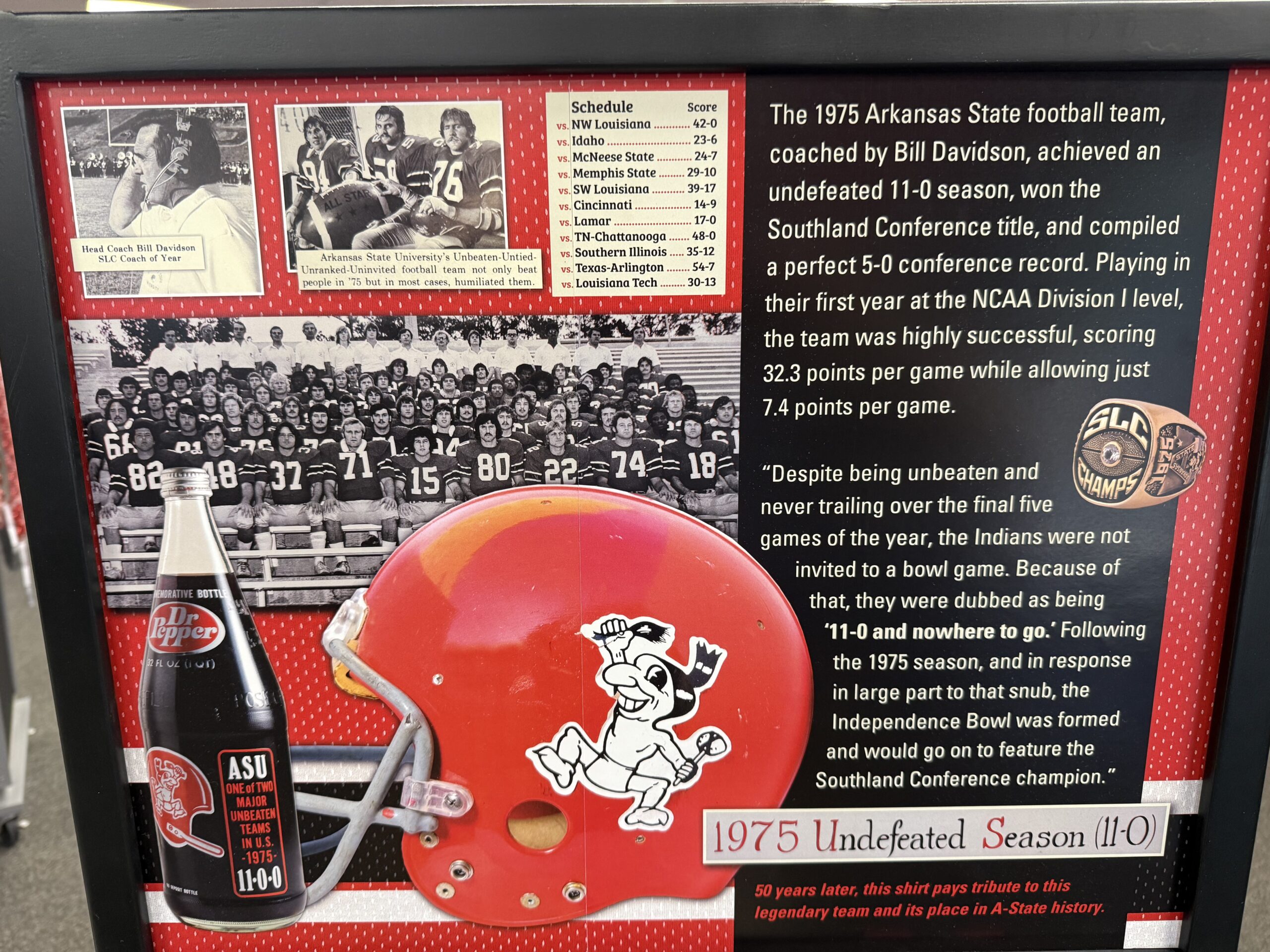

In 1975, Arkansas State football went a perfect 11-0. While the season began with a week one win over Northwestern State, it began to take shape long before.

Quarterback Question Marks

When people think of a prototypical quarterback, they usually picture someone who is tall, possesses a strong arm, understands the position, and can throw on the run. If your quarterback does not possess at least two of these traits, success could be hard to come by.

But in 1975, Arkansas State needed something different. Head coach Bill “Bull” Davidson had his mind set on a new offensive game plan: the veer option. The origins of the concept come from former Houston head coach Bill Yeoman.

The veer typically operates out of a split back set, but the option added another layer. It allowed the quarterback to make a decision based off of three reads. He could keep the ball, give it to the back running up the middle, or pitch it to the back trailing him out wide. While the concept was born from the split back formation, Arkansas State evolved the play into their preferred I-formation. The option, along with one other play, would go on to become offensive staples for the team.

“What they also wanted to be able to do was run the 52-53 lead play, which was just the fullback leading the tailback through the hole through the middle,” Wiley said. “The other thing they’d like to run was 30-31 trap option.”

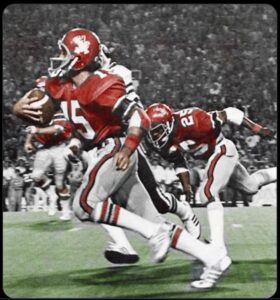

With the ingredients needed to successfully run the option all in the cart, Davidson had one more box to check on his grocery list. Who would play quarterback? He turned to senior David Hines, who ran a similar offense in his high school days. There were three problems. First, Hines stood at just 5’9″ – far from the desired 6’3″ or taller so many coaches covet in their signal callers. Second, he didn’t possess a particularly strong arm. This was less of a problem– with the option, Arkansas State would be running more anyway.

“I did throw the ball actually,” Hines joked. “I just threw it backwards!”

The final problem, and the most glaring: Hines wasn’t exactly a quarterback. In fact, he wasn’t even an offensive player in his first three seasons in college.

Hines was a safety. No wonder he wasn’t getting reps under center.

He stumbled into the role early in Spring ball. When one of the quarterbacks was out sick, Hines threw some passes during practice. He thought it would simply be as a stand-in, but even after all the quarterbacks were healthy, the team’s offensive coordinator told him to keep throwing. Hines was none the wiser.

“I still didn’t have any suspicion,” he said. “But then after that spring practice… Davidson wanted to see me in the office.”

Going into the meeting, Hines still had no idea what was about to happen.

“He just started out by saying ‘we want to try you at quarterback,'” Hines said.

Hines immediately accepted the offer. After all, he was a football player, and wanted to help the team win any way he could. He had just one condition.

“Coach, I still get to return punts right?” Hines asked.

Davidson replied with an emphatic “Oh yeah.”

It was the one promise Davidson failed to keep.

Without any junior or senior quarterbacks on the team, Hines believes the staff went with him due to his leadership and experience. Perhaps the most important quality of a quarterback is one that observers might not be able to see on tape. Leadership is the extra, sometimes unseeable, quarterback trait. Clearly, Davidson and his staff saw that in Hines. When you’re running the veer option, those physical tools can take a back seat if the man commanding the huddle has the respect of the ten players surrounding him.

1975 was the first season Arkansas State competed at the Division I level. The basketball and track teams had high expectations. People knew the football team would be good, but Hines’ inexperience at the quarterback position gave some people pause in saying just how good.

Early Season

Arkansas State cruised through the early portion of their schedule. They outscored Northwestern State, Idaho, and McNeese by a combined score of 89-13. The option was working to perfection.

“Hines became a magician,” Wiley said.

During practice, the offense would line up against the same defense that gave up those 13-combined points during the opening stretch. Playing against a front seven featuring six NFL draft picks made the offensive line even better.

“You had to realize they played against a great defense every day,” said defensive lineman Robert Speer. “Us.”

Hines agreed with Speer.

“The best defense we played all year, bar none, was our defense in practice,” Hines said.

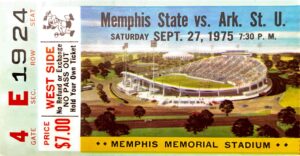

Despite winning each of those games by multiple scores, the team was an underdog heading into a road matchup against mighty Memphis State (now University of Memphis). Memphis sat at 1-2, but had earned a win on the road against #7 Auburn two weeks earlier. Nobody gave Arkansas State a chance.

The team didn’t care.

“The coaches instilled in us such a confidence that you didn’t look at who they beat or who beat them,” linebacker Jerry Muckensturm said. “Do what you’re supposed to do and things will work out.”

Reporters asked Davidson if he thought his team could hang with the Tigers. According to Hines, Davidson told the media the following:

“We’re just going to come over there in two yellow school buses and just hope we can stay on the field with you guys.”

Not only did they win, they dominated. In a 29-10 win, the defense recorded five interceptions. The highlight was a Roy Painter pick-6. On his way into the end zone, the speedy defensive back waved goodbye to Memphis’ fastest player, Keith Wright. It was a moment that still sticks with many players.

“Painter was probably the fastest man on our team,” Hines said. “I think he was doing that to Keith Wright because he wanted Wright to see if he could catch him… Nobody caught him.”

The following week, Davidson made an odd decision. He decided to try throwing the ball more. Hines’ lack of experience showed, as Arkansas State fell behind. He threw three interceptions in the first half, prompting the usually quiet Ken Jones to speak up. Hines remembers jogging back to the sideline next to Jones. The All-American guard turned toward his quarterback.

“Run the f-ing ball.”

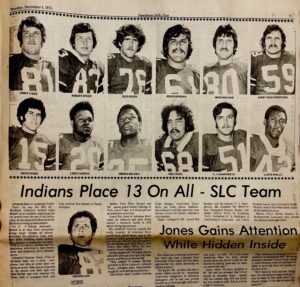

The football colloquialism ‘ground-and-pound’ feels like it was created to describe Arkansas State that season. Behind their two star guards, Jones and T.J. Humphreys, the team rushed to the tune of 340.5 yards per game to lead the entire nation. Over the full season, that was good for 3,745 yards and 42 touchdowns. Tailback Dennis Bolden ranked 13th in the country with 1,191 rushing yards. 87% of the team’s total offense came courtesy of their rushing attack.

After the halftime break, they ran, ran, and ran some more. The deficit quickly evaporated, giving way to a 39-17 win.

“What was good about our games back then is that they weren’t very long,” Speer said. “Running that clock, eating it up with five yards of dust.”

Arkansas State was leaving their opponents in the dust, but would find themselves wading through water just a week later.

“The Duck Game”

Two weeks after thumping Memphis State on the road, Arkansas State traveled north to face Cincinnati in their next-toughest test of the season to date. Cincinnati hosted Memphis earlier in the season, handing them a 13-3 loss. The game would be the closest game Arkansas State played all season, but the story of the game didn’t involve the players.

Usually, a football game will feature 11 players lining up on each side of the line of scrimmage. The whistle will blow, the ball will be snapped, and the two sides will fight with every ounce of energy to gain just one extra yard.

But on Saturday, Oct. 18, 1975, the 22 players were not alone on the rain-soaked field. Through the heavy drops of rain extra spectators invaded the field. They didn’t look like typical football fans. They traded out their jerseys and hats for beaks and webbed feet.

Puddles built up on the AstroTurf, creating a perfect landing zone for ducks. While some Cincinnati players were stunned by the aquatic birds they now shared the field with, Arkansas State’s players felt right at home.

“We’re from the south, we’re used to duck hunting,” Speer said. “I’m surprised we didn’t try to shoot ’em!”

Arkansas State went on to win, 14-9. While they escaped with their perfect record in-tact, their quarterback did not come out unscathed.

Hospitalized Hines and Arkansas Camaraderie

When Hines and Arkansas State headed home from Cincinnati, the quarterback had a significant cut on his elbow. He slid on the flooded AstroTurf, dying the puddles with a red undertone as the skin on his elbow peeled back. While he didn’t feel anything in the moment, the same could not be said by the time Tuesday rolled around.

“I woke up and my elbow was the size of a softball,” Hines said.

By Thursday, Hines was in the hospital. He received steroids, and was rushed to the team plane on Friday. He did not plan on seeing the field against Lamar, but plans changed late in the third quarter.

Backup quarterback Randy Reed went down with a head injury. Davidson turned to Hines.

“Can you go?”

“Yeah.”

Tough as a nail, Hines battled through the rest of the game. Fullback Leroy Harris had a standout performance with Hines running the option. Arkansas State won 17-0. By the time the team returned to Jonesboro, he was back in the hospital for the rest of the night.

“That was probably the most disappointing part,” Hines said. “I wanted to go party.”

While the A-State quarterback recovered, his teammates celebrated the win. The players lived together in the same dormitory, and after wins they would all “go down the road.”

“This was a dry county,” said Muckensturm. “Either someone would go down the road and make a trip and buy some beer, or we’d go to Roy’s.”

Whoever made the beer run would bring the drinks back to the dorms. They would either stay in their rooms or go to the pavilion on campus. Drinking was not permitted, but the players had a workaround.

“We decorated our rooms with empty beer cans,” Muckensturm said. “The coach would come in and we’d put our beers that were full next to the empty ones and they couldn’t tell.”

The team, made up mostly of Arkansas natives, grew incredibly close because of their housing arrangements and backgrounds. Many of the players were also part of the same recruiting class, 1972, and had been together for four years. Muckensturm believes the camaraderie they developed off the field helped them become a better team on it.

“Sports brings you close together because you go through the same thing,” he said. “We were like brothers. On the field, if one person got beat, the other person is not going to.”

On Sunday, Hines was released from the hospital. He might have missed a night of drinking, but he ensured his health for the rest of the season. It would not be the last, or most spectacular, celebration of the year.

Louisiana Tech

Arkansas State would go on to rattle off three dominant wins over Chattanooga, Southern Illinois, and UT Arlington. The team was one game away from an undefeated regular season and a Southland Conference title. Its final challenge was Louisiana Tech.

LA Tech had won the Southland the past four seasons. Coming into the game, they had an 8-1 record– the only loss coming to Southern Mississippi on the road. In Tech’s five seasons in the conference, they had not lost to a Southland opponent… until Arkansas State came to town on Nov. 29.

“We had a confidence that no one was really going to be able to beat us,” Muckensturm said.

All season, the defense felt like they could beat everyone straight-up. Defensive coordinator Mike Malham Sr. would call in what the players described as “fancy” defensive packages. The calls would often come in late. In the huddle, Muckensturm and fellow linebacker Mike Malham Jr. (Malham Sr.’s son) would simplify the operation.

“He’s seeing his dad hesitating,” Muckensturm said of Malham Jr. “He would always yell at me ‘just run 5-2 regular!'”

For Malham Jr. and Muckensturm, affectionately known as “The M&M Brothers,” 5-2 regular was Arkansas State’s bread-and-butter call. It was simple: beat the guy in front of you and go after the ball.

Malham Sr. coached his players to make NFL-level decisions. Muckensturm played in the NFL for seven seasons, and credits his defensive coordinator for easing the transition.

“[Malham Sr.] had us really disciplined,” he said. “Read the linemen, and they’ll take you to the ball.”

The Arkansas State front-seven also learned how to terrorize their opponents on special teams. Defensive end Jimmy Lisko worked tirelessly to find gaps in kick protection. He blocked a whopping eight kicks (four PATs, three punts, one FG) in 1975 alone. The team blocked 11 in total. Both stand as NCAA records to this day.

“He had studied that film, if you want to call it film back then,” Speer said. “He just wanted it.”

The Louisiana Tech game would be the toughest challenge of the season for the defense. Coming into the game, Tech was averaging 31.6 points per game. They would finish the season as the 14th-best scoring offense in the country. Arkansas State’s defense finished the season third in the nation in scoring, holding their opponents to 7.4 points a game. They won the battle, holding the high-flying Louisiana Tech offense to just 13 points in the 30-13 victory. It was Tech’s lowest-scoring game of the season.

Arkansas State had gone perfect.

11-0 and Nowhere to go

After flying home to Jonesboro, the team was gearing up to celebrate. Davidson announced that kegs of beer were waiting for his team at the pavilion. Nobody was going to miss out on this one. Not Hines. Not even the coaches.

“We got to go drink with the coaches,” Hines said. “I don’t think anyone pulled out a cigarette in front of them, but the beer was flowing that night.”

The festivities did not last long. Arkansas State soon found out that, despite going undefeated, they were not selected for postseason play. In 1975, only 11 bowl games existed. Since the Southland Conference was new to the Division I level, they did not have an automatic bowl bid for the conference winner. The Independence Bowl was created the next year– in large part due to their snub.

“We wanted to go to a bowl game so bad,” Speer said.

While the team overcame every challenge thrown at them, they wanted something more. They had not played a ranked opponent. After finishing as the No. 21 team in the final AP poll, they felt like they could have held their own.

“I really wish we could have played a ranked, notable team,” Muckensturm said. “We had a special thing going here.”

In 1976, Arkansas State did not win the Southland title. The conference sent two seniors from each team to the inaugural Independence Bowl game. Speer and Painter Arkansas State’s representatives.

“They kicked that ball off, I looked at [Roy], he looked at me, and I said ‘let’s go home,'” Speer said. “I don’t want to sit here and watch this because it should have been us.”

“Losers Fall Apart, Winners Stay Together”

While the 1975 season did not end with a bowl game trophy in the hardware cabinet in Jonesboro, the season accomplished something more important. It guaranteed that every member of the team would stay in touch for the rest of their lives.

“Losers fall apart, winners stay together,” Speer said.

He brings up a good point. There will never be a reunion for the 2008 Detroit Lions or the 2017 Cleveland Browns. Teams that truly mean something to their community and organization live on eternally.

“Now we’re going to each other’s funerals,” Speer said. “But back in the day, we were going to everybody’s weddings and watching their kids grow up. I’ve got a group text of 20 of my teammates and we still talk every day.”

The one person who slipped through the cracks? Wiley. He was like a ghost. Wiley was as unfindable as anyone can be in 2025.

“I’m not on social media,” he said. “I’ve got too many fish to fry.”

Brad Bobo, the Arkansas State associate athletic director for marketing and fan engagement, found something in the 1975 media guide. The document told him where to look. 50 years ago, Wiley had a one-year-old daughter. Bobo took to Facebook. He found her, and by association, found Wiley.

Hines was on the phone with me when I mentioned Wiley’s name. His inflection immediately changed.

“Do you have his phone number?”

Hines was eager to reconnect with his old friend. They had not talked since that 1975 season 50 years ago.

Perhaps Wiley will be sitting at that same desk when he hears from Hines. The room might be a little less cluttered. The books might be on shelves and the boxes might be put away. But for the time they share a phone call and reminisce about that fateful season all those years ago, Wiley won’t be in that room.

He’ll be back in Jonesboro, reliving the moments that made 1975 so special.

That was a tremendous article, Christian. I really, really enjoyed it.

I met Hines when I was 7, going on 8 in ’75, and you better believe my plastic red helmet had the number 15 on it.